On Vigdis Hjorth's "Will and Testament"

Also some words on Knausgård, and some words taken from emails

This is Sintext IX. Thanks for reading. At the bottom you can find buttons to share this issue, or to sign up to get the next one in your inbox; there should also be a link to unsubscribe.

This issue is mostly a reflection on Vigdis Hjorth’s 2019 novel Will and Testament, translated from the Norwegian by Charlotte Barslund.

Then you’ll see 18 first lines excerpted from emails that my sister, a rising junior in college, received over two days last week.

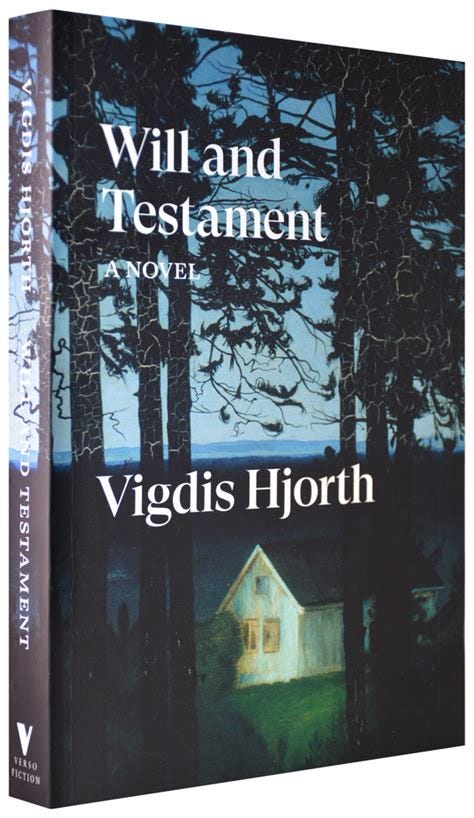

Will and Testament, by Vigdis Hjorth, trans. Charlotte Barslund, Verso Fiction, 2019

Like a sleeve caught on a branch, I’m stuck on a sentence. It’s on the 303rd of Will and Testament’s 330 pages: “I bought a bracelet of black beads, a mourning bracelet, and I wore it from bar to bar in San Sebastian, looked at it and remembered Dad’s death and my grief.”

The sentence first snagged me with its rhythm. The low percussive cadence, the battery of Bs, pitched my attention forward, onto the place my lips meet. There the third comma lulled me, such that the last predicate, the last two objects in this not-so-long sentence, took me by surprise. Pronouncing the f in grief left me biting my lip. The sentence first snagged me with its rhythm, then it held me fast with its implications. I’ll come back and explain what they are.

The “I” is the only speaker in the book. Her name is Bergljot; she’s a theater critic and playwright in her 50s. Will and Testament opens with an inheritance dispute that impels Bergljot to deliver her side of the story. We learn that Bergljot’s parents promised all four of their children would inherit equally, yet they mean to leave the two summer cabins to their two youngest daughters alone. When their father dies, Bergljot and her older brother, both estranged from the family, decide to fight the below-market buyout they’re offered. But there’s an underlying reason the family is so divided, a division the cabin dispute belies. This is the subject Bergljot creeps toward over the novel’s course, encroaching past the family line in the sand until the secret—that Bergljot’s father sexually abused her when she was a young girl—is submerged in her narration.

Bergljot represses those memories until she is divorced with three kids herself. The trauma resurfaces as waves of debilitating physical pain. Bergljot only understands what’s happening when her unconscious slips the truth into a one-act play: “there it was, in between all the other words, and I had a shock, I was floored, and at one fell swoop I turned into someone else, forever changed into another by this moment of truth.”

Bergljot begins psychoanalysis and confronts her family. Her father denies it. Her mother—vain, neurotic, utterly self-insufficient—had long mistrusted her husband, but sides with him anyway. So does her youngest sister. Bergljot eventually heeds her closest friend Klara’s advice and severs herself from her parents. For over 20 years—until the cabin dispute—her only link to the nuclear family is Astrid, the third sister, a human rights worker. She passes word of developments that would be significant to a member of the family: celebrations, surgeries, deaths. Bergljot interprets Astrid to be ever insisting that it’s on the black sheep to rejoin the flock.

Will and Testament, Hjorth’s 37th book (I know), was a bestseller in Norway, where it came out in 2016. It’s natural to read Bergljot—a literary-minded, middle-aged woman, fluent in Freud and Jung, with a parallel family structure—as Hjorth’s stand-in. It’s also clear why the obligatory comparison is to Karl Ove Knausgård, Hjorth’s compatriot and fellow practitioner of “reality literature,” as their country calls fiction correlating closely with real life. Critics received their works with similar acclaim, and tabloids digested them with similar enthusiasm.

Social norms are what make the comparison obligatory. Hjorth shares with Knausgård a literary notoriety born of impropriety: Each upended their families for literature’s sake—prompting book-form responses from siblings and exes—and scandalized a society that believes it’s “typically Norwegian to be good,” as Bergljot quotes a former prime minister saying. Bergljot could also have quoted her own aversion upon first meeting Klara: “I didn’t want her eccentricity to rub off on me.”

Luckily the comparison remains helpful when seen through a formal lens. Hjorth and Knausgård both rely on parataxis—joining clauses together without articulating how they bear on each other, writers often pivot from place to place on punctuation alone, the goal is to enforce juxtaposition as the reader’s mode of perception—in order to convey the sensation of undifferentiated thought. Wayne Koestenbaum has observed that “any reader of contemporary culture is contaminated by paratactic energies”; slogans attest that he’s right. Hjorth and Knausgård use this priming grammar of association to send their narrators spinning back through time; both are also champion digressers. Their similarities even extend to a shared fixation on mundanity in general, and the travails of domesticity specifically. It’s no wonder why reading their books elicits an overlapping set of polarized affects: boredom and stimulation, revulsion and identification.

Then the comparison runs out of road. Their common strategies are the products of different ambitions altogether. Knausgård sought to escape his midlife, writerly crisis by laying himself bare on the page; Hjorth took up her identity in order to tease out what it looks like when certain people treat each other a certain way. So it is that My Struggle spills out over ten times as many (transcendent, bad-sentence-ridden, still-my-favorite) pages as Will and Testament needs in order to say more of substance about folks other than its author. There’s nothing extraneous in Hjorth’s storytelling. She favors short passages, which let her break the claustrophobia of Bergljot’s repetitions with ample blank space. She also puts genre to good use. Will and Testament isn’t autofiction—a genre with particular traditions of French origin, which My Struggle happens to typify—for the simple reason that Hjorth’s protagonist doesn’t carry her name. Hjorth instead chose more opacity between Bergljot, her reader, and herself. “Reality literature” presses the button down to the level of confession, but exits the elevator before the doors close.

And beyond genre, there’s the matter of gender. I mentioned both authors’ attention to domesticity. Knausgård’s marks him as a writer of feminine literature, as Siri Hustvedt discussed in an essay worth reading from 2015. Hustvedt places Knausgård’s transgression in its national context, where “misery memoirs are not fashionable.” She also explains the torrent of attention in terms of the gendered stakes: “a man who reveals his feelings is at greater risk of being shamed for those revelations. He has farther to fall.” The question becomes who else is celebrated for laying bare controversial emotions. “Any and every story sinks or swims in the telling,” Hustvedt knows, “but still it is fascinating to think of My Struggle as a narrative of what Simone de Beauvoir famously called ‘becoming a woman.’” Will and Testament isn’t such a narrative. “More than a book about sexual abuse,” even, Hjorth has said her novel “is about what it’s like to not be heard.” That Hjorth built the scaffolding from demanding material—from incest, yes, but also from a fictionalized version of herself—shouldn’t keep us from seeing this central drama.

I think an equally fruitful comparison for Will and Testament, then, is something like Mary Gaitskill’s This Is Pleasure. Her 2019 novella is a duet of subjectivities that emerge when an articulate man’s history of flagrant sexual misconduct costs him his career. Gaitskill relays the events from two startlingly coherent perspectives: that of Quin, the disgraced male book editor; and that of Margot, a female editor who happens to be his best friend. Margot contains within herself the love to remain supportive, but also grapples with a private fury. Towards the end of the novella, Margot recalls the “strange, muted combination of incredulity and acceptance” she’s felt since Quin tried to find the silver lining in her own childhood sexual assault. Margot and Bergljot’s experiences obviously diverge, but Gaitskill and Hjorth both harness the narrative force of female frustration.

I found Will and Testament to be refreshingly straightforward; it’s a book of moral clarity that often encapsulates its lessons in single sentences. Family is circumstantial: “He trusted me with his coat because we had once been squashed into the back of a car with our sisters.” Bergljot owes nothing to her sister Astrid, or to anyone else who refutes her reality: “there are opposites which can’t be cancelled out, there are times when you must choose.” There will be no rapprochement without a reckoning: “It is sad, I said, but I can’t make it not so.” Bergljot will continue to experience pleasure amid her lowest lows, regret entangled with her fiercest principles: it is “possible to exist in two states simultaneously.”

Each of these lessons is embodied in that sentence I’m still stuck on: “I bought a bracelet of black beads, a mourning bracelet, and I wore it from bar to bar in San Sebastian, looked at it and remembered Dad’s death and my grief.” Sentences like these don’t happen by accident. They’re the work of a writer in full control of her language, and a translator who intuits exactly what that language wants to do. The implication’s in that third comma, distributing the weight of the sentence unevenly. The implication’s in that final conjunction, using and to separate rather than join. Such sentences, with their many meanings, are what let Will and Testament be both readable and profound.

Image sources: 1) Verso; 2) New Statesman.

18 First Lines Taken from Emails My Sister Received Over Two Days, Who “Really Wishes Emails Weren’t the Primary Source of Communication”

It has been a rocky two days for us all.

I should have done this a while ago.

I will be hosting a help room session tomorrow morning from 9AM to 10AM EST.

We hope this finds you getting some time to reflect and rest now that you've completed the Spring 2020 semester.

We are excited to introduce you to your professional moving service.

Hello! I hope you are able to get outdoors and enjoy the sunshine even in these difficult times.

Thank you for shopping with us. We’ll send a confirmation when your items ship.

We hope that that this unusual and difficult semester ended well for you and that you and your family are staying healthy

Oh NOOOOO!

A quick reminder to register for the pack/store/ship move out option

We have a teeny tiny favor to ask of you: pllllllllease fill out this quick survey.

As the pandemic continues to upend the energy and transportation industries, Duke energy and environment experts told the media Wednesday that policymakers should use the opportunity to reshape environmental policy.

Spero che tutto stia andando bene per tutti voi.

I’m glad the sound was better this afternoon. I’ll reboot my router regularly, in case that was the problem.

we hope this finds you safe and healthy during this unprecedented time.

I sent the email to the wrong class list, so sorry.

I’m sorry (and embarrassed) about the audio failure this morning.

Over these past few months, the world has seen the best of Duke.

In the next issue, the tenth, I’ll be taking stock of Sintext so far. I want to plot how I feel about what I’ve shared in this space. Whether you’re a new reader or old, if you have thoughts, suggestions, observations, or recommendations, I’d welcome them as always. I very much appreciate you reading, liking, sharing. (And if you have similarly evocative first lines of emails, send them along! Could be fun to have a recurring segment.)

Sintextually yours,

Marc