Hi! Thanks so much for reading the first issue of Sintext proper. If you missed it, here’s the introductory post. In this newsletter, you’ll find: ~1,000 words on an upcoming memoir about the excesses and iniquities of the tech industry; a brief burrow into a recent viral tweet pertaining to Baby Yoda; and a few thoughts and thanks related to getting this newsletter up and running.

If you haven’t provided me with your email, do so now! Before I make you marginally more aware of your online behavior!

Reading

Uncanny Valley, Anna Wiener; MCD; Jan. 14, 2020; 288 pp.

“Do you think you hate yourself?” a therapist asks Anna Wiener near the end of Uncanny Valley, near the end of her time working for San Francisco startups. Wiener deflects. She tells us instead of spending the next day reading tweets from venture capitalists “about the unlocked economic potential of the urban poor.” She concedes this “wasn’t exactly an act of self-care.”

Uncanny Valley, Wiener’s first book, is partially an account of the cost incurred on a society that has given itself to the tech industry to mold. It’s partially an account of the cost incurred on women who want to help decide what shape society will take. It’s also the full account of the author’s own complicity, the story of how her ambition got the better of her judgment.

I knew, even as I was moving through them, that I would look back on my late twenties as a period when I was lucky to live in one of the most beautiful cities in the country, unburdened by debt, untethered from a workplace, obligated to zero dependents, in love, freer and healthier and with more potential than ever before and anytime thereafter—and spent almost all of my waking hours with my neck bent at an unnatural angle, staring into a computer. And I knew, even then, that I would regret it.

Wiener lands her first tech job in New York, at age 25, when she ditches literary agency assistantship to help three men — who, in what becomes a trend, are even younger than her — “disrupt” publishing. Their business plan amounts to little more than commodifying the services of a public library; Google eventually swallows the company to the tune of eight figures. But Wiener is let go long before then. As the CEO accidentally admits in the company-wide chat, her problem is that she’s “too interested in learning, not doing.”

By now Wiener has caught on to tech’s “speed and open-mindedness,” its “optimism and sense of possibility.” She moves to San Francisco to become the 19th employee at a data analytics startup. The only imperative at this company: you must be “Down for the Cause.” And, for a while, Wiener is down: “I was happy; I was learning. For the first time in my professional life, I was not responsible for making anyone coffee. Instead, I was solving problems.”

As part of the Solutions team — customer support, in the patois — she’s responsible for “helping men untangle problems they had created for themselves.” Though this comes to feel “like immersion therapy for internalized misogyny,” the work never pushes Wiener to a breaking point. Neither does the realization that she works for a surveillance company, which dawns on her gradually, grudgingly, even after collecting client metadata so comprehensive they call it “God Mode,” even after Snowden blows the whistle on the NSA. Wiener begins considering a new job after her callous CEO makes her cry, and informs her that she’s “not analytical.”

I quote so much for a reason. When Wiener contrasts her lucid narration with this sort of understated inanity, she’s reminding us to put pressure on the “garbage language” of Silicon Valley, to see through its expedient mixtures of euphemism and hyperbole. She relays how a beloved ex-coworker — “a curly-haired twenty-six-year-old with a forearm tattoo in Sanskrit and a wardrobe of workman’s jackets and soft fleeces” — is reteaching himself to say application, because the “abbreviation obscures that it’s software.” More conspicuously, Wiener subverts the world’s foremost brands by refusing to name them. It’s easy to decipher who she means by the “online superstore” or “multinational consumer-electronics company” or “social network that everybody hates.” It’s harder to remember what services these corporations were originally supposed to provide.

Wiener eventually leaves Big Data to join an “open-source startup” still reeling from a gender discrimination scandal involving its first female engineer. Here Wiener continues to support customers, a task that now includes monitoring the company’s chat rooms and digital repositories. Soon after she starts, her team discovers a suspiciously well-organized group of trolls hosting files on their platform; these are the perpetrators of Gamergate. Her education continues until the 2016 election, where all such stories end.

I expect this book will sell really well when it’s published next month. It’s got buzz: find it on January’s IndieNext list. It’s got blurbs: Jia Tolentino calls it “a definitive document of a world in transition.” It’s also impeccably written: Wiener has an eye for the damning details that signify all of a culture’s shortcomings. (“Multiple startups raised money to build communal living spaces in neighborhoods where people were getting evicted for living in communal living spaces.”) Her eye and her ear — for lists, for punchiness and pith — are why Rebecca Solnit and Ed Park liken Wiener to Didion, a comparison that normally feels lazy for female nonfictionists.

In many passages, Uncanny Valley preserves the mordant tone of its earliest published form: short fiction (!!!) in n+1. That piece earned Wiener the book deal, which was promptly optioned in early 2018, around the time she quit the open-source startup to write full-time. (Must narratives appear as memoir before we heed their lessons? Must books appear on screen before we deem them entertaining? Or fully capitalized?)

If you just want the tea, it’s all in this excerpt, which ran in an October issue of the New Yorker. And I’ll make it even easier for the sleuths among you. The open-source startup is a thinly veiled GitHub: Wiener gawks at the mock Oval Office and Situation Room originally built into their HQ. It took patronizing the “search-engine giant,” but the data analytics company is Mixpanel: she mentions ghostwriting copy for a feature called “Addiction,” every part of which is unbelievably on the nose. But even as Wiener spills it — even as she lays bare her industry’s sexism, pervasive “[l]ike wallpaper, like air”; its dual tendencies towards the frivolous and the cutthroat; its unmatched hubris — she avoids the vindictiveness of a tell-all, the rectitude of a crusade.

In a podcast supporting the n+1 piece, Wiener describes her disposition towards Silicon Valley as somewhere between the usual attitudinal poles: “mean” and “boostery.” This third space she occupies feels a lot like ambivalence in the literal sense: attraction and repulsion at once.

Maybe it’s because Wiener continues to live in SF, among the people she made characters; maybe it’s because she still reports on tech-sponsored public spaces and tech-spawned housing crises; maybe it’s because she wants us to understand that tech is one of the vanishingly few sources of hope today; maybe it’s because she now claims a perspective clearer than the prism of a bubble; or maybe it’s because she’s fundamentally decent; whatever the reason, the fact is, all judgment passed in Uncanny Valley is first filtered through Wiener herself. And that’s what makes the full memoir worth reading. Because that third space, to be clear, is what we mean by the private. This space is where the ambiguities that make us human are preserved. This space is more valuable than any profit.

Related readings

The NYT piece I linked at the end of my review, that I’m explicitly linking again, because it’s a very important documentation of a process that shouldn’t surprise anyone who has been paying attention (s/o Lora!!!)

Another NYT piece on an Oakland homeless encampment

These downward tilted toilets, designed to maximize productivity and ruin poop breaks

Snackpass’s Series A (so well-deserved!), led by Andreessen Horowitz, who also led Substack’s, and GitHub’s, and Mixpanel’s (if you’re going to click any of these last four links, click that last one, just read the first few paragraphs)

Sofar Sounds as the inevitable result of pumping VC money into DIY house shows

This paragraph in Conde Nast’s updated privacy policy, which arrived in my inbox as I was getting ready to publish this: “While we generally do not obtain other Personal Information that is often considered ‘highly sensitive,’ such as biometric information (e.g., fingerprints, facial recognition images), financial account information (e.g., bank account, credit, debit or other payment card numbers or other financial information), government issued identification numbers (e.g., social security number, drivers’ license number, passport number, or state identification card number), insurance policy number, or medical, health or insurance related information, we may do so when such Personal Information is necessary to offer you certain services.” ¯\_(ツ)_/¯

The transcript of Sacha Baron Cohen’s keynote at last month’s ADL summit

Rabbit hole

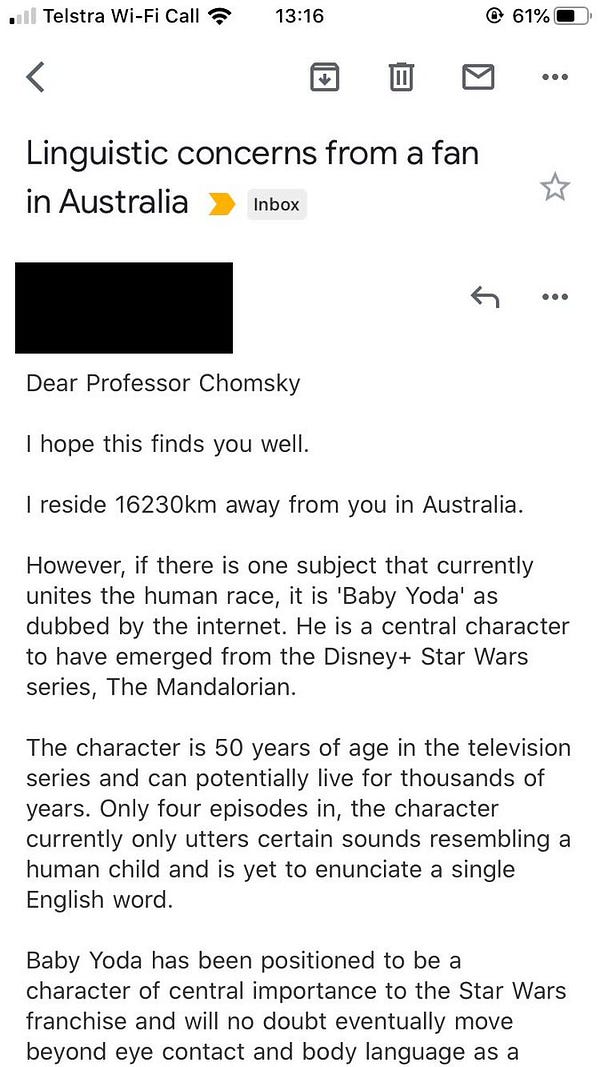

If you don’t tweet Noam Chomsky’s reply to your email, did it really happen?

(The screenshots are long, feel free to skim.)

I saw this on the “microblogging platform” a couple weeks ago. I was likely in bed, just after waking up or just before going to sleep, the terrible times I always check Twitter. Which is to add context for when I say that it reaaallly riled me up.

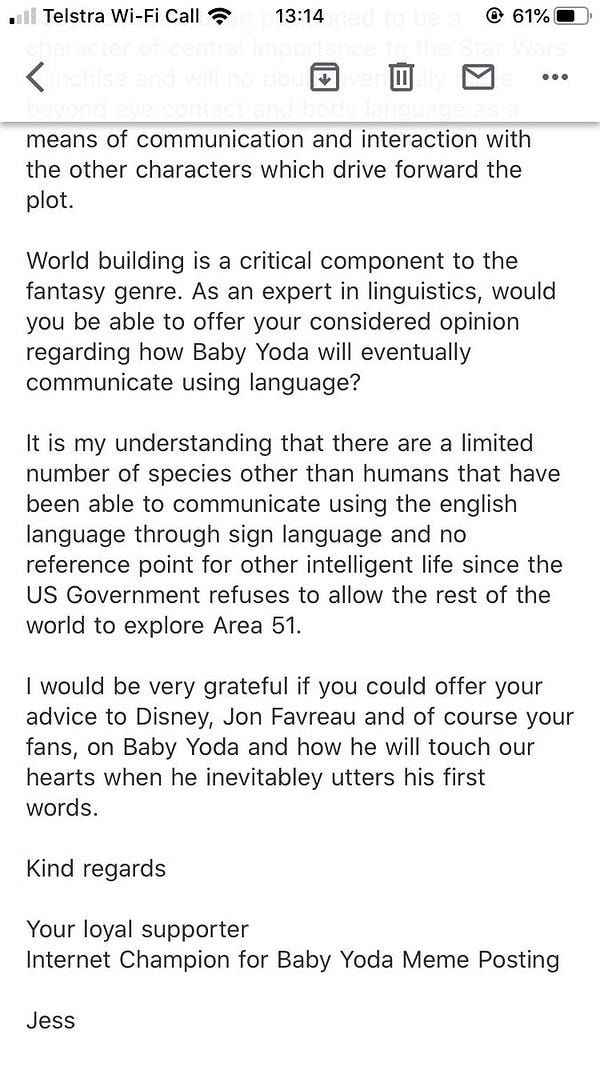

I earmarked the tweet, and when I returned to that cursed application I love so well, my annoyance had mellowed into a line of inquiry that centered on Chomsky himself: Why are people bothering him with questions as dumb as “any thoughts on memes?” Shouldn’t he be worrying about more important things? He really does answer any email sent his way, doesn’t he? Should I email him and ask him how he feels about people bothering him with dumb questions?

Instead I did some research. I waded through some Reddit threads, which ranged from wholesome to appalling. I read the follow-up articles on the tweet in question. I discovered that… the whole exchange may not even be real? (It turns out that user had no prior tweets. We can’t all be prolific.)

And, eventually, I came across this gem of a clip, which stopped me in my indignant tracks.

The particulars of Yoda speech aside (which are actually pretty interesting to me), “Jessica” wrote her email in the language of college meme pages, in the mode of community formation. Either you get it (i.e. you watch The Mandalorian and don’t care that Baby Yoda is a Trojan horse Disney will use to take your money) or you’re not in on it. I know I’m a killjoy, but my point is that I’m not in on this particular joke — and that’s a shitty feeling. With Ali G, on the other hand… with him I’m willing to laugh at Noam Chomsky’s expense, though he handles it with grace, bless his heart.

The need to consult experts is deeply entrenched in the culture. (I vaguely remember something from APUSH about the Gilded Age and efficiency and specialization.) It’s why I’d cold-email professors during my lackluster stint as a campus journalist (s/o Harold; at least my article on Snackpass aged well). Sometimes I’d go to their office hours, or even grab a coffee. Other times, their email response would contain expertise enough.

I still think it sucks that this is the sort of thing that goes viral, that publications like Business Insider and A/V Club need virality for sustenance, that feeling left out hurts so much. At least I understand my visceral response to this particular tweet a little better now?

Reflection

If you’ve gotten this far, thanks for bearing with me. Corralling my many thoughts into readable prose of a reasonable length was harder than expected. (Was it readable? Was it reasonable? You can reply directly to the emails you receive and let me know. I’d love specific feedback on seeing sentences bolded intermittently.) I’m very surprised that my first newsletter mentions the position of CEO three times now. I also didn’t foresee the immediate gratification of starting this project, the pleasure of receiving support.

Right now I’m at 103 subscribers and counting. Among those people: my mom’s friend from college, who shipped me books all the from Mexico on every birthday until I was in college myself; teachers from Heschel, my elementary and middle school, whose influence I’ll never be able to fully comprehend; friends a few years older who’ve shown me how rewarding newsletters can be to read, and also happen to be kickass journalists; peers who now work at some of the companies I mention, who might be able to more immediately put their bodies upon the gears; and a few people whose emails I didn’t even recognize.

A big thank you, also, to the folks who informed me that I’ll need 9,000 new followers before I can link to this newsletter directly from my Instagram story. Eh, I’ll try to figure something else out.

Sintextually yours,

Marc