Don't let this flop #ForYourInbox

Decoding the real structure of feeling in screenshots, TikToks, and memes

As promised, this is Sintext VII.2—here’s the first part, breaking down Welsh Marxist multi-hyphenate Raymond Williams’ theory of cultural analysis. Given the media embedded in this issue, reading it on a web browser might be smoother than through your email client.

Also: I’ve set up a Sintext affiliate page on Bookshop.org. Collected there are/will be the books discussed in this space, as well as those that have been tacitly underpinning my thinking. But if your local bookstore continues to handle orders—DIESEL even lets you browse shelves remotely now—please continue purchasing directly through them.

2. Representing realities

I offer two suggestions to take into our constant encounters with contemporary cultural texts. The first is to allocate the same breadth of aesthetic and social consideration for digital popular culture as we do for high culture. The second is to deal with art—with any work claiming to interpret our lived experience—as if our ability to shape our own systems of significance is under duress.

For Williams, studying a past culture means approaching its documentary record with an eye towards reconstructing the prevailing structure of feeling. We’ve absorbed his teaching to a certain extent: When we read about fine art or literature, we expect to read of the circumstances in which it was produced and to which it responds. With popular culture, however, we’re less inclined to root around for the contextual light it might shed. Only decades after its heyday does a song or cartoon or hemline become an artifact of its era. This is cultural negligence.

Out of what exists at a given time—popular or arcane—it’s obvious that only “certain things are selected for value and emphasis” and reproduced. Less apparent is that this process of selection is equally a process of rejection, of leaving for dead “considerable areas of what was once a living culture”; or that these “certain things” and “considerable areas” could be monetary policy and transportation habits as much as much as they are slang and trendy recipes—each, in its own way, contributes to the felt sense of life at a particular time and place. Control over the selection and rejection of the many parts, then, is control over the direction of the whole. Taking up the lens of cultural analysis means seeing the “real nature of the choices we are making”; it also means coming to terms with the real nature of the choices we aren’t making—cultural negligence, too.

Cultural production looks a lot like a feedback loop: what represents our structure of feeling is selected as tradition, and what’s selected as tradition then informs our structure of feeling. My focus here is on the forms of individual agency that already exist in online popular culture—on the means we have to plug into that loop.

2A. Screenshots as user-generated friction

I took this screenshot on April 10. As I write, on April 26, 1.67 million cases is now 2.95 million, resulting in not 101,000 but approximately 205,000 deaths, with more than 860,000 patients recovered. One day—not soon, but eventually—those numbers will stabilize, and the information on that page will be up-to-date. The yellow pop-up box will appear elsewhere, or not at all. The story will stabilize.

But we will have records of what it literally looked like when the story still shifted beneath our feet. If it’s impossible to see the numbers under constant revision themselves, the next best thing is evidence that the invisible battalion of Wikipedia editors—whom we trust as much as journalists—has mobilized. This image is transience preserved.

The designers chose a color for their notification box just a shade darker than French’s mustard yellow. It signals intermediacy but also danger—nothing’s happened, per se, but time has passed; this iteration of the page is no longer hospitable because it no longer portrays the world. This image is also honest design preserved.

Then there’s the cartogram—a map that represents statistics graphically—atop the ride sidebar, in which the darkest red (for now, for once) corresponds with the Global North. This is also visual evidence against American exceptionalism—Covid-19 will align domestic attitudes quite differently than 9/11.

There’d be no way to isolate an outdated page for scrutiny without screenshots, which also go by other names: screen grabs, screen captures. All imply violence, which suits the jarring nature of the technology. Only screenshots do what photography used to: freeze a single frame of experience. To update Sontag, screenshots “really are experienced captured… the ideal arm of consciousness in its acquisitive mood.” Screenshots acknowledge that experience itself is already contained within the screen—that the digital world is the real world.

Apple (maker of my hardware) introduced a function not long ago that further individuates the screenshot. After capture, your image appears in a bottom corner—it hovers there for a moment, asking to be dealt with right away, shared and deleted so it doesn’t join the regular photos in your camera roll. With social screenshots we replace summaries. We pass along chains of texts, DM conversations, entire threads, posts on private pages, content behind paywalls; some people are even prone to posting their bank balance. Screenshots attenuate our expectation of privacy by turning the isolated digital encounter communal; they match our privacy norms to the possibilities of technology.

Or maybe this quick-share function is meant to remediate the flow of computing, already interrupted by the act of screenshotting itself: The manual contortion required on both phones and computers is a relief from the incorporeality that is being glued to a screen. It’s as if digital design is slowly weaning us off our meatspace analogues: The iPhone camera ditched its skeuomorphic shutter years ago, leaving behind only a ghostly click. Screenshots put us back in our bodies, back behind our eyes, attending to the image we want to capture, if only for a moment.

Then there are screen captures of a different sort.

My generation doesn’t watch cable news, yet we’re aware of its outsized influence on those who do. The few bits we consume come to us incidentally—at the gym, in the company of relatives—or else through social media, as captioned snippets, prepackaged for transplantation from one habit-forming medium to another. Those bits are enough for the aesthetics of cable news to embed themselves in our sense of power’s look, sound, and source.

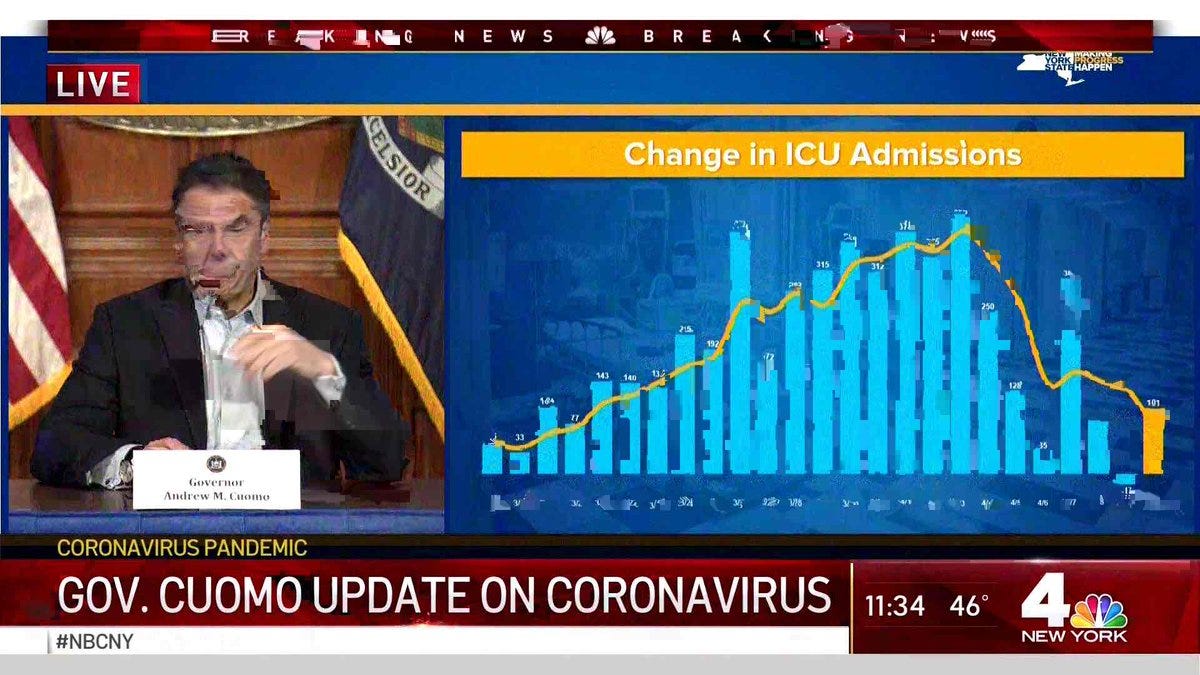

Anthropologists like Shannon Mattern have discussed the surreality of Cuomo’s slideshows. Sure, they “project a reassuring image of managerial order,” but what lingers is the resonance of their “motley aesthetic”:

[It] mirrors our own confusion and disorientation—our uncertainty about how to spend our days trapped indoors, about which sources to trust, and about the proper role of the state and its institutions at a time when our immune systems, our public health infrastructures, our electoral politics, and capitalism itself reveal their terrifying precarity all at once.

I think that description is astute, but it’s hardly self-evident. We need careful observers to yank paragraphs of meaning from the televisual stream. Screenshots slow it down for us—it’s easier to latch on to still images, to study them like paintings when they’ve been manipulated, stripped further from their usual signifying channel.

The Twitter account @GlitchTVBot posts dozens of similarly distorted stills each day. It seems to not answer DMs, so I only have my hunch that the bot generates them itself. A glitch art technique called datamoshing seems likely, which cuts stable frames from a compressed video file: “Delete the image data—all the identifiable, still images of the video—and you’re left with the abstract, interior information that populates the space between images.” You’re left with interstitial essence—the guts of TV.

I really wouldn’t know if this sort of distortion occurs often on cable. When I stream TV, I’m interrupted only if I press the wrong button on the Roku, or if the power goes out. Thankfully, seeing glitched-out stills is enough to not only break up the monotony of my Twitter feed, but also remind me of the materiality of my phone screen itself: it’s pixels all the way down.

I also detect a certain insolence in these corrupted images—they could be visual counterparts to sPoNgEbOb TeXt, minus the ableism. Cuomo’s blurred face evokes in me the same sort of zoomer churlishness that so pisses off boomers: You think you’ve seen enough graphs, enough politicians; we think you’ve watched enough TV.

Oxford American Dictionary has glitch as a “a sudden, usually temporary malfunction or irregularity of equipment.” The noun became popular amid the space race, in the early ’60s, when the public heard astronauts use this Yiddishism to describe minor mishaps. Its English origin actually dates back to the golden age of radio operators, at least twenty years prior. The word has always been used first by technicians. Then, once it has accumulated the veneer of authority, it’s deployed in managing the expectations of the masses. “It’s just a glitch”—it’s a problem that will fix itself.

Biden’s primary candidacy hinged on an untenable promise he seems to still believe himself: Trumpism is a glitch in our democracy, an aberration that will disappear come November; all we have to do is wait. If we don’t understand what caused a problem, the mindset goes, then it can’t be our fault—and if it’s not our fault, it’s not on us to keep it from recurring. When some leaders feel impotent, it’s their instinct to abdicate responsibility altogether.

This is the same attitude many of us hold towards technology. Glitches distinguish users from developers—those whom technology exploits from those who exploit technology. I’m firmly in the former camp, dependent on the benevolence of the code that governs so much of my life. The only philosophical aspect of development I remotely understand is design. In the idiom of user experience, friction is any impediment to effortless task completion. Often, frictional features are included on purpose: needless progress updates assure us that our tax software caught every last break; sign-in scans slow down so we trust our bank’s security measures. Patronization is codified, misunderstanding encouraged.

I think more meaningful are the frictions that occur unbidden, that we users capture.

Warzel writes for The New York Times; his tweet quickly attracted a Twitter team looking to troubleshoot. It turns out that the thumbnail updated itself by periodically scraping (screenshotting!) an image from a live news broadcast. In this case, the program worked perfectly; the mistake was in the design itself.

Despite the straightforward explanation, the prevalence of moments like these—when everything is kosher, yet you really can’t believe your eyes—explains why paranoia is so widespread; our sense of normalcy is continually upended by real events, on- and offline. Instead of adjusting our expectations, or finding conspiratorial causes, it’s imperative that we continue to define wrongness on human terms.

The same applies to our sense of rightness. My friend Mariah Kreutter has written persuasively on how artist Hito Steyerl’s concept of the poor image—“the debris of audiovisual production, the trash that washes up on the digital economies’ shores”—suits life under quarantine, when the closest we can get to friends is through the screen, by interfacing with “moving images, copies in motion, pixelated, freezing, and out of sync. As Steyerl predicted, the degraded picture quality acts as another layer of information. The time and condition under which these images were created is embedded into their very form.”

Remember that Williams makes this same point: it’s precisely an artwork’s singularity that says so much about its culture. Mariah puts it more eloquently: “The idea that an image can convey nothing about the conditions under which it was produced is a fantasy.” The Twitter program wouldn’t have had Epstein’s face to scrape if we didn’t already sensationalize celebrity, or revel in death.

The lesson I take from the poor image, from the glitch, from the screenshot: the forms that most faithfully represent a broken world will themselves seem “broken.” In truth, they work just fine.

2B. TikToks and memes as affective mirrors

There’s this is what it looks like and there’s this is what it feels like. With screenshots we’ve worked at the former; with memes and their progeny we’ve mastered the latter.

According to Williams, structures of feeling aren’t shared between generations, in part because they cannot be formally taught: “One generation may train its successor, with reasonable success, in the social character or the general cultural pattern, but the new generation will have its own structure of feeling, which will not appear to have come 'from' anywhere.” In reality, a new structure of feeling emerges not spontaneously but gradually, after enough younger individuals interact enough times with what we experience as a different culture:

the new generation responds in its own ways to the unique world it is inheriting, taking up many continuities, that can be traced, and reproducing many aspects of the organization, which can be separately described, yet feeling its whole life in certain ways differently, and shaping its creative response into a new structure of feeling.

We have already updated our creative response. But because it circulates online—detached from the traditional modes of assessment and commodification—digital popular culture has only recently gained the exposure it merits, to bite the online language of exploitation. Now, many more people find themselves reliant on systems of cultural production sustained through the internet alone. As Drew Austin writes in Kneeling Bus, “We live in the white cube now; anything that relies on a specific source of external context is an endangered species.”

Publications have acknowledged that the internet is the spine of contemporary culture, but they don’t have a feel for how youth will affect the curvature of the whole body. The Times employs a journalist, Taylor Lorenz, on the internet culture beat. She regularly interviews TikTokers, meme czars, digital-forward agents, other influencer industry randoms. But her editors and audience seem contented with lifestyle roundups. While tracing online behavior is invaluable, what’s missing is coverage that sustains an interpretation of what that behavior actually means; what’s lost is how younger generations metabolize the world—how our cultural response actually relates to our own structure of feeling.

The platforms themselves make it all the more complicated to decipher. Jia Tolentino, one of my favorite writers, tackled TikTok in long-form last fall. She focused on the parent company’s history, sped along by its $75 billion algorithm. The app is unparalleled in how it “seems remarkably attuned to a person’s unarticulated interests. Some social algorithms are like bossy waiters: they solicit your preferences and then recommend a menu. TikTok orders you dinner by watching you look at food.” The next step in predictive technology is the total automation of desire.

What’s heartbreaking about TikTok is the clarity with which posters intuit their fundamental helplessness. Because TikTok posts spread to strangers rather than acquaintances, their only guides through the void are captions and hashtags. The most common caption, “Don’t let this flop,” exhorts the viewer to take action and prevent the poster’s work from being wasted. The near-universal hashtag—#FYP, meaning the “For You” page, the personalized feed—is a prayer offered at the altar of algorithmic whim.

I think the opacity of social algorithms will eventually become a major issue, and the argument to regulate tech companies as public utilities will pick up steam. Meanwhile, the algorithm will continue to serve its function: Tolentino explains that it “gives us whatever pleases us, and we, in turn, give the algorithm whatever pleases it. As the circle tightens, we become less and less able to separate algorithmic interests from our own.” This is the natural endpoint: human and machine blur, and our sensibility becomes like that of a cyborg rodent; you submit to TikTok, the “enormous meme factory, compressing the world into pellets of virality and dispensing those pellets until you get full or fall asleep.”

But guess what! This framing is facile, too, because it doesn’t account for what gets posted in the first place—the line between consumption and reproduction is murkier than we think.

Memes are as much moods as they are imitable units of experience—and so much more than pellets of virality. Memes are indeed great at compressing and transmitting some of the world’s complexities: irony, self-awareness, multiple layers of reference. They’re also terrible at preserving others: nuance, general legibility. Memes are magic mirrors that speak volumes, but only to those who see themselves reflected.

What if it is? What if this TikTok represents where we’re right now? It’s not a bad candidate—everybody’s cooking and washing their hands, everybody’s seen Ratatouille, everybody feels foreboding. These are the features that older folks can identify with. But the memes they’re used to consuming are husks devoid of substance—humor without heft.

Calling memes “art” is itself a meme (see @ArtDecider, with 200K followers), but I think this particular TikTok qualifies because of how it assaults the senses: with quick cuts, with choice shots of TV (Cuomo again; his slide reads “The bad news isn’t just bad”), and, most of all, with volume. Of course it’s unlikely that the sound was mixed to this effect; ask the poster and he’d say he was just trying to make a funny TikTok. But I’d argue that the sudden intensity is why this short video makes so many TikTok users feel seen—and is what in turn propelled it to virality. It’s really a question of giving ourselves credit.

My favorite recent meme is the coffin dance. It’s a simple format: a video of festive Ghanaian pallbearers is set to the drop of a 2010 EDM track, then juxtaposed with footage of imminent catastrophe. The meme’s appeal is as much schadenfreude as it is a twisted form of collective self-deprecation. Here’s the original TikTok that started the fad, and below is a Twitter compilation with some viciously funny examples.

The second mashup in the thread shows what looks like a rocket-propelled grenade failing to launch (it cuts away before impact). What sticks out to me, after too many views, is the watermark near the bottom right corner. This footage, taken God knows where, ended up in some foul corner of the internet, where it was found by someone trying to build a brand.

Meme gatekeepers are as anti-democratic as the algorithms they surf; they make it so that memes can be astroturfed. Luckily, it’s not so much specific memes that stick around as it is their formats—and the ones that do are ultimately those that strike at our structure of feeling, which is always organic in origin.

Despite our keen awareness of death right now, watching people be seriously hurt is somehow still funny. If coffin dance lasts, does it mean our felt sense of life skews towards morbid amusement? Journalists have cited Holocaust jokes as precedent, but the intermixing of horror and humor really is a propensity native to the younger generations. We’ve figured out how we want to respond—not only creatively but also emotionally—to the unique world we’ve inherited. So it is that we answer disparate difficulties with the same blend of performative nihilism and resilient pleasure that’s become our signature. (For the vagaries of global finance, see stonks. With school shootings we ask, first time?)

I think memes work in a similar way as datamoshing in that they use technology to force the face of a disagreeable world into more appropriate contortions. It’s a strategy that might bode well for our ability to stave off existential paralysis, an experience that will recur for the rest of our lives as the climate crisis worsens. No algorithm can show us how to do that.

Throughout this issue I’ve been leaning on a few other implicit assumptions. I’ll make them explicit now. One is that the culture we consume always has social implications. Right now is an unusual time for the human faculty of attention. The further it’s expropriated, the more vital even passive resistance becomes.

Two is that assessing culture along the axis of entertainment—liking, sharing without comment—isn’t enough. We need more people talking confidently to each other about what they’re seeing, thinking, feeling. Critical consciousness needs to be raised at the level of the individual user, and fostered through meaningful digital interaction. I’m trying to make this newsletter one such exchange.

Three is that when I say “we” and “our,” I’m now thinking specifically of people close to me in age, who already lean left. Tied to that is my belief that the cultural work I’m asking for can only be done by groups whose structure of feeling is best represented in popular digital culture.

Four is that I’m missing tremendous swaths of the internet: not just sites where billions gather—YouTube, Twitch, reddit; I didn’t even mention Instagram—but also parts of Twitter and TikTok to which I’m not privy. We can’t teach a structure of feeling, but we can work on democratizing the tools of cultural analysis.

None of what I’m saying is new. The last word is from Williams, updated to the present tense:

To put on to Time, the abstraction, the responsibility for our own active choices, is to suppress a central part of our experience. The more actively all cultural work can be related, either to the whole organization within which it [is] expressed, or to the contemporary organization within which it is used, the more clearly shall we see its true values.

I appreciate you reading. I’d also appreciate you liking, commenting your thoughts, and (especially!) sharing this with others who’d get something out of it. If you’d like to reach me, just respond to this email. I’m always thrilled to hear from you.

I’d also love to open Sintext to more voices. Interested in contributing? Do get in touch.

I’ll be back in two weeks, hopefully with a review of something lighter.

Sintextually yours,

Marc