I spent this week shopping for new clothes. Coats, jackets, sweaters, button-downs, tees, tanks; trunks, shorts, jeans, pants, slacks; underwear and socks and shoes, too. Many options in the catalogue. And these are just the basics. Uncountable combinations. Not that there’s any need to count. In truth they’re all variations on a single theme.

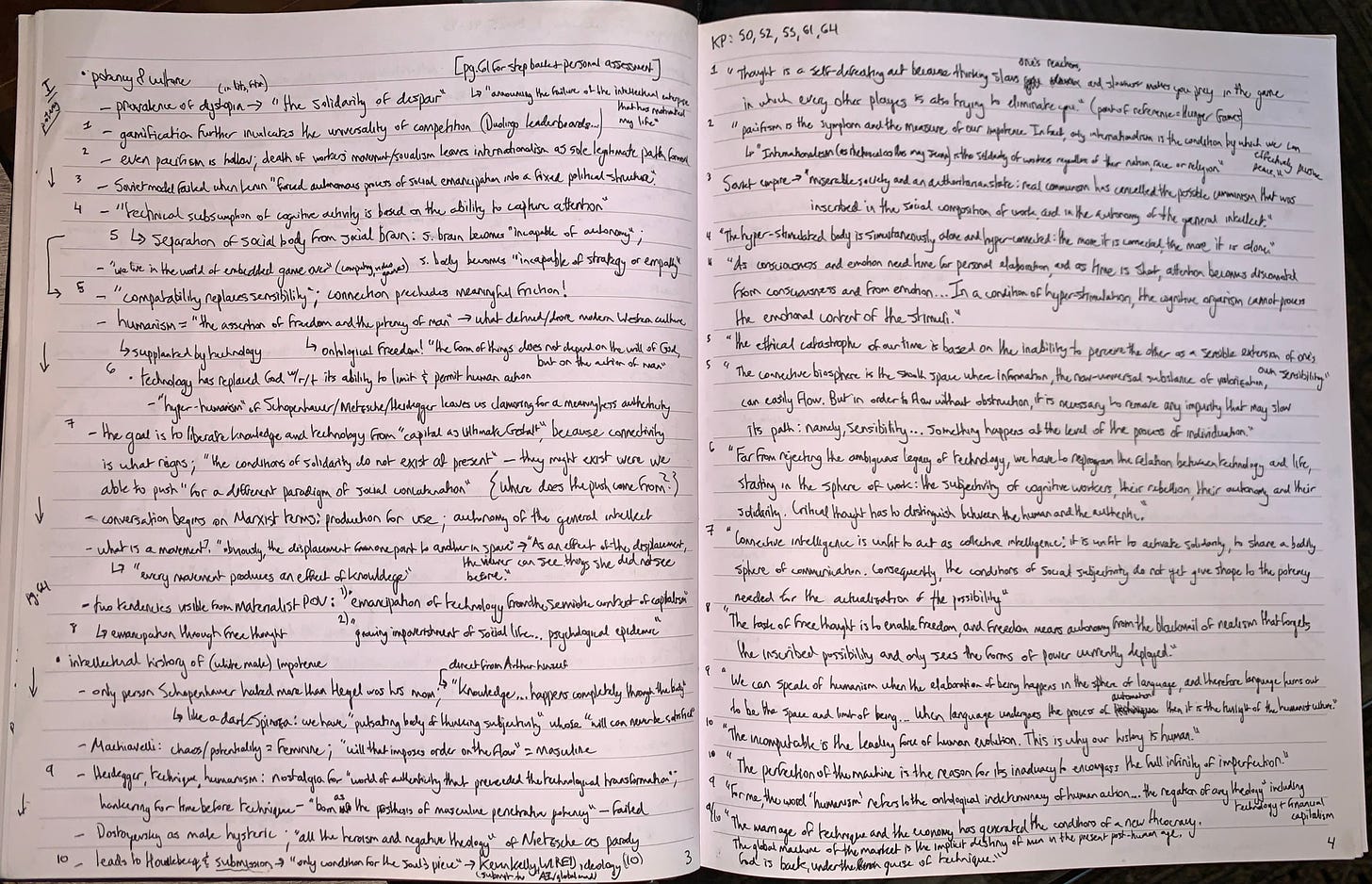

Most of my hours passed with one Italian designer. Franco “Bifo” Berardi. He’s older now, but his vision’s still clear. His needle as sharp as ever. He was very influential in the late ’70s. Ran a sort of renegade boutique, part of a wider collective, Autonomia. They drew attention. The fallout forced him to France for the ’80s. By then a competing aesthetic had won out. Overseas, we never got to wear his signature style.

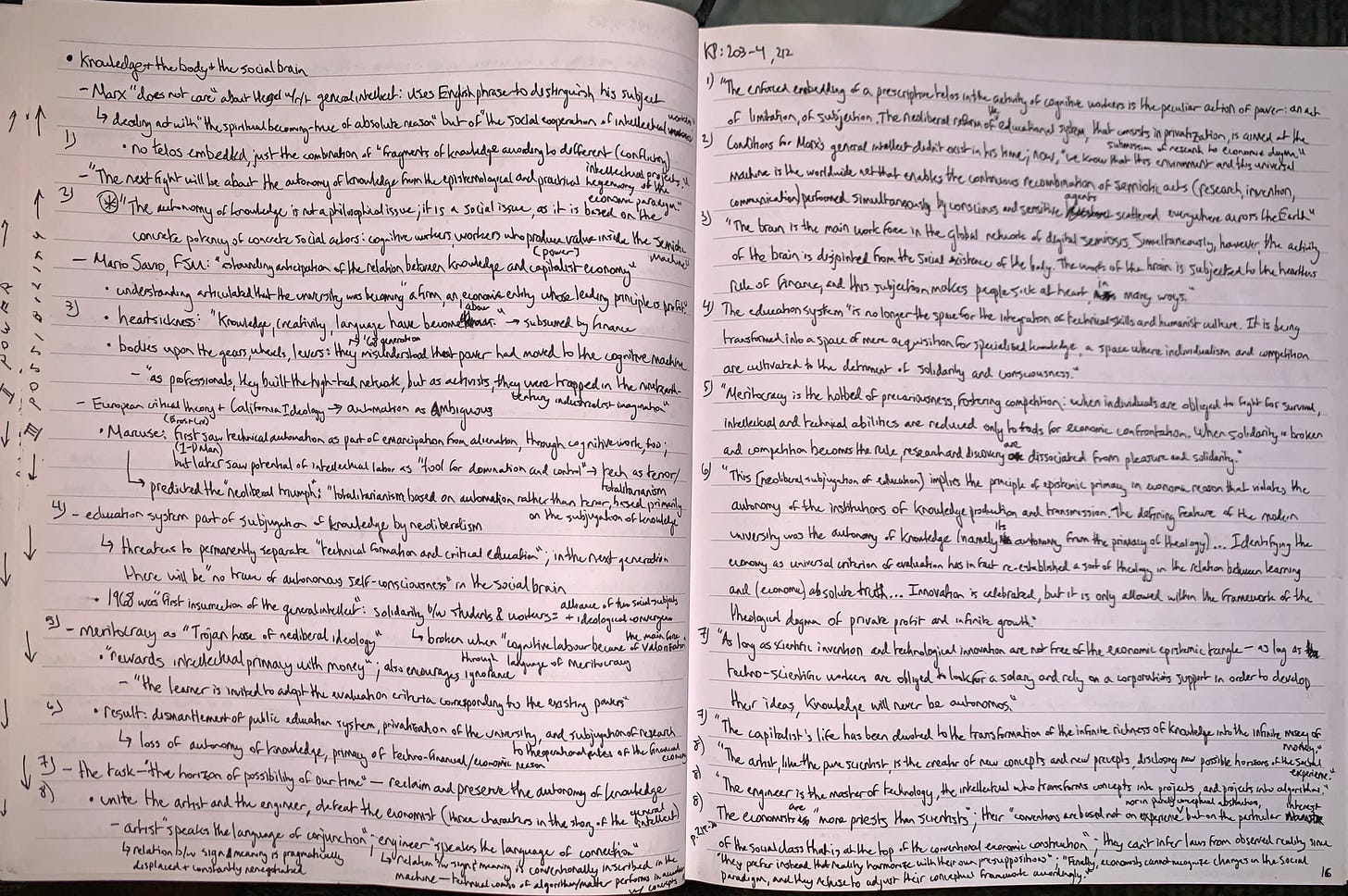

I’d like to share what I cobbled together from his 2017 collection.

But first let’s talk about the weather.

On May Day, Tim Bray quit his job. His employer had been firing employee organizers. First warehouse workers, then engineers. So, Bray took a moral stance. “Bye, Amazon,” he wrote on his blog.

In name, Amazon axed those employees for violating company policy. In essence, “it’s clear to any reasonable observer that they were turfed for whistleblowing.” For blowing the whistle on being treated like replaceable parts, “fungible units of pick-and-pack potential.”

On Wednesday, two journalists and an activist—Rachel Cohen, Alex Press, and Dania Rajendra—spoke of labor action against Amazon. They noted several truths: A worker has died of Covid at the Staten Island warehouse where Christian Smalls worked; warehouse workers only work under the present conditions because they’re desperate; Amazon has a large pool from which to replace workers not desperate enough; those warehouses have long been brutal places to work; Bray spoke out when Amazon began terminating engineers.

Bray was a VP at Amazon Web Services. Directly related to deportations, maybe, but not to the warehouse workers. Yet they’re who he sought to platform: “Any plausible solution has to start with increasing their collective strength.” Quitting cost Bray more than $1 million, he thinks. Better that than “signing off on actions I despised.”

One more observation, then I’ll walk you through my look: You’re wearing clothes right now. I was wearing clothes last week. We are always already wearing clothes.

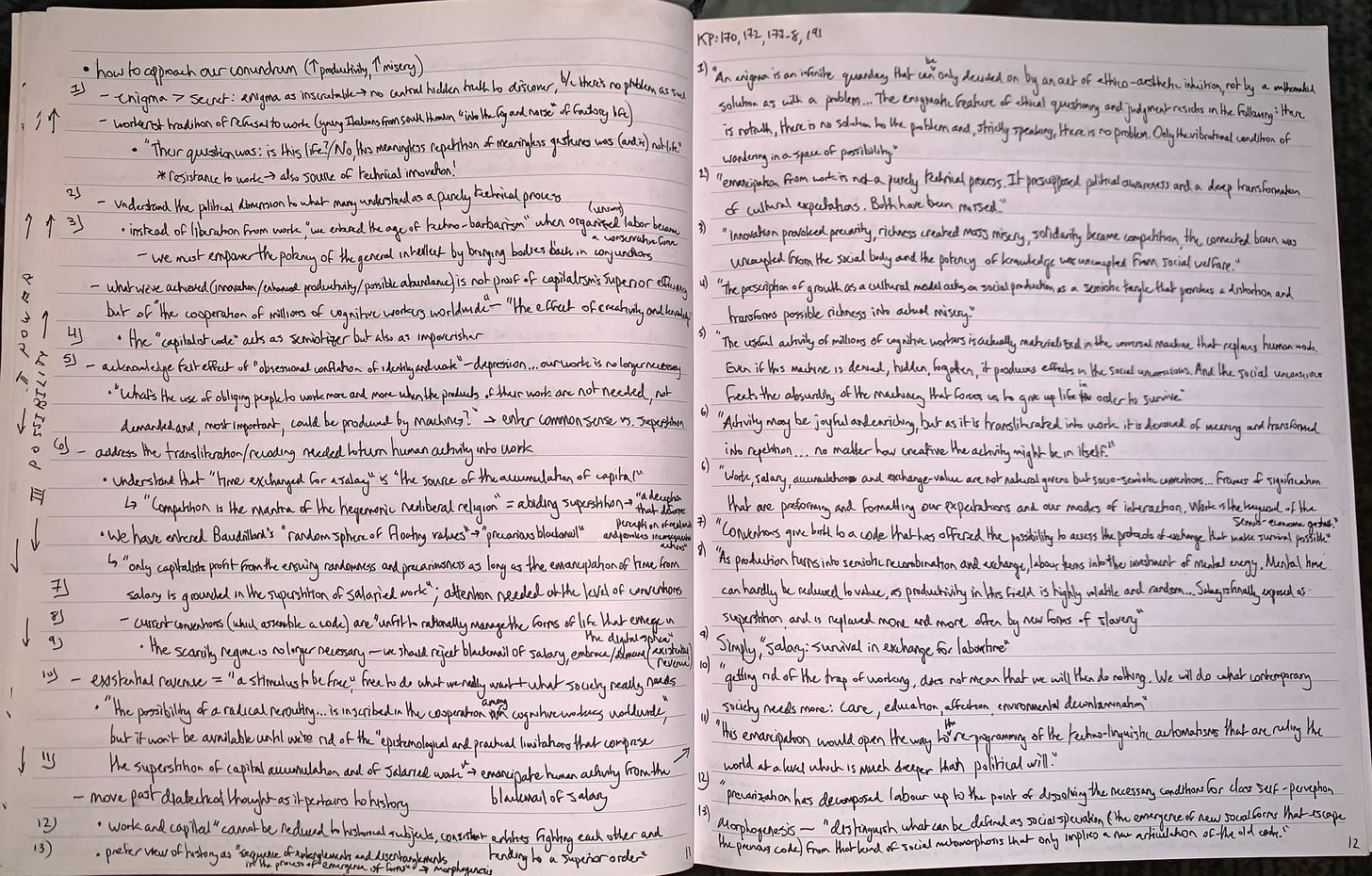

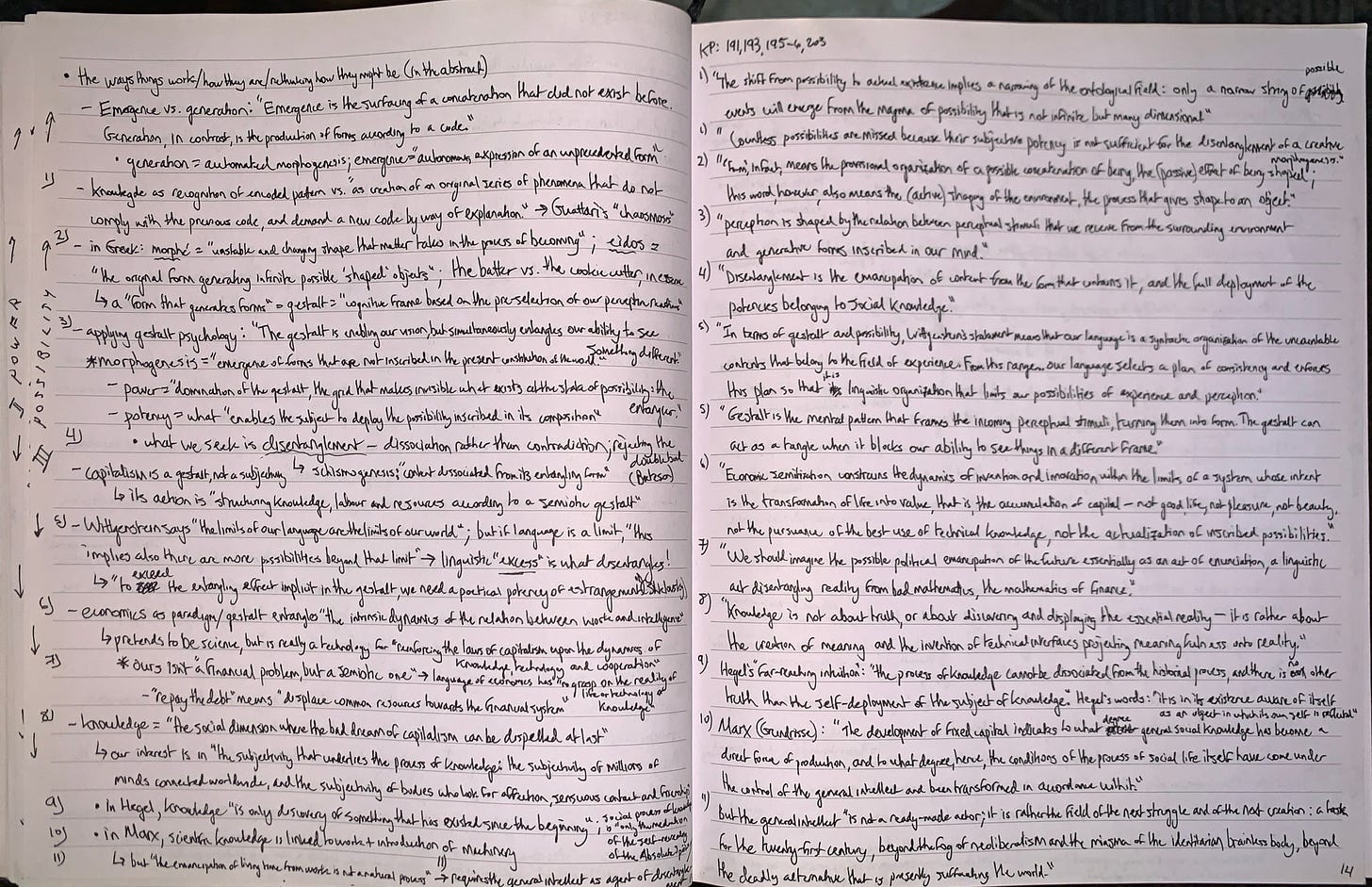

Okay. As outerwear I’ve got intellectual understanding of the failure of the promise of modernity, and also economic semiotization constrains the dynamics of invention and innovation within the limits of a system whose intent is the transformation of life into value, that is, the accumulation of capital—not good life, not pleasure, not beauty, not the pursuance of the best use of technical knowledge, not the actualization of inscribed possibilities. It’s lighter than it looks, and does a great job keeping me warm and dry.

Underneath that, draped across my torso, friendship is the force that transforms despair into joy. I like that it’s tight on my chest but leaves my arms bare.

Around my legs, the automation of linguistic interaction and the replacement of cognitive and affective acts with algorithmic sequences and protocols is the main trend of the current mutation. A tad loose, so it’s cinched by the technical subsumption of cognitive ability is based on the ability to capture attention around my waist.

Peeking out are my socks. Surfing the wave of this age on my left foot, mapping the currents of tidal change on my right. (It’s hard to tell they’re mismatched.) My boots are the autonomy of knowledge is not a philosophical issue; it is a social issue, as it is based on the concrete potency of concrete social actors. I’m big on practicalities, like grip.

I also picked out an accessory. The ethical catastrophe of our time is based on the inability to perceive the other as a sensible extension of one’s own sensibility. It reminds me of the woven bracelets I’d wear after summer camp until they rotted off my wrist.

Last, and you’ll have to take my word for it, but what I put on first, what I take off last, what keeps all else in place, what escapes my grasp, what I cannot see, what I cannot imagine, what I cannot even conceive is the means of escape.

I’ve never pulled off a fit like this.

Last week, Ben Tarnoff published a long article called “The Making of the Tech Worker Movement.” He tells how people like Tim Bray came to stand with people like Christian Smalls.

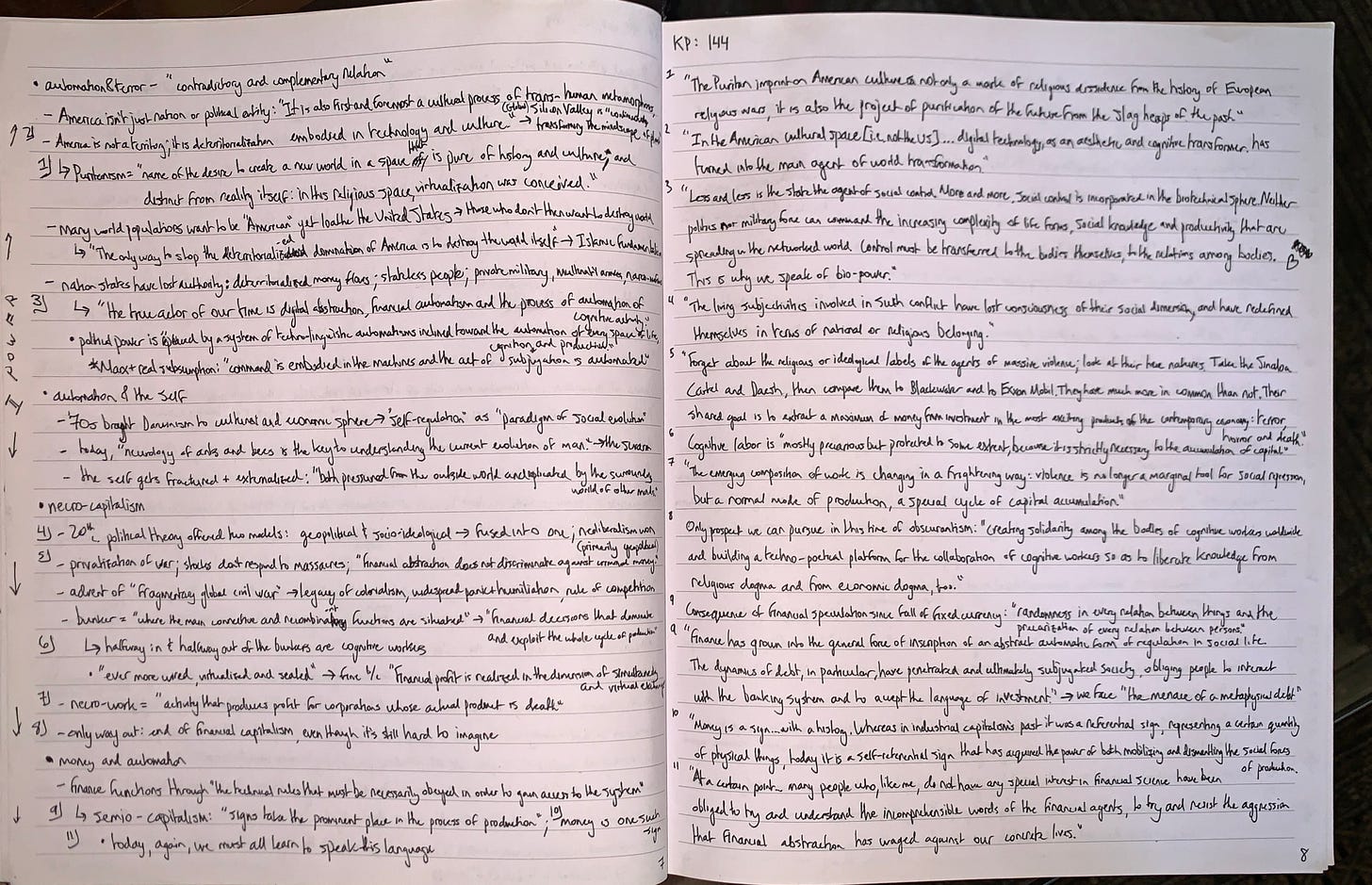

Consider the different kinds of tech workers. There are subcontracted service workers: janitors, cooks, drivers. Then subcontracted office workers, also precariously employed, though they “sit at a desk and move symbols around on a screen.” And finally there are full-time office workers. The ultimate task of the tech worker movement is to help those full-time office folks see themselves as “not professionals, creatives, or entrepreneurs, but workers.”

Tech workers who are minorities tend to get it the quickest. They’re acquainted with alienation, with the distance of power. (Bray pointed out that everyone Amazon fired is female, not white, or both.) After 2016, more workers understood their fundamental lack of “control over the investment and production decisions of the firm.” Coalitions formed, petitions circulated; now conflict escalates.

A small detail from my guy in Milan, could decorate any office, the existence of the working class is not an ontological truth: it is the effect of a shared imagination and consciousness.

Berardi favors flounces and flourishes. It’s why he’s so fun to wear. His designs immunize you against intimidation. Equip you with unlikely equanimity. Help you surprise yourself in the mirror without first wanting to flinch.

Do his designs take getting used to? Sure. Some of his stitches come loose if you pick at them. His pieces tend towards transparency, leave you feeling indecent. His reds are particularly challenging. Or maybe that’s just the American in me talking. I’m not used to feeling sexy, looking loud. I like it so far.

Outfits can’t tell you where to go, but the ones worth wearing can teach you to walk. Wearing Berardi I know how to hold myself under the weight of the world.

Tech companies like to promote fixes that don’t address why there’s a problem to begin with. They like to pretend software can plug holes in a ship that’s sinking because we swapped out social care for competition. Evgeny Morozov calls this “solutionism.” Solutionism is the good cop to neoliberalism’s bad cop. “Neoliberalism shrinks public budgets,” yes, but “solutionism shrinks public imagination.” That’s what we should fear.

We don’t actually think “we learn more about the world when we act as consumers than when we act as parents, students, or citizens.” We don’t actually think “our human needs are better expressed in the consumerist language of competition than in any other terms.” Solutionism insists otherwise. It inculcates the belief that digital technologies can “disrupt and revolutionise everything but the central institution of modern life—the market.” A belief economists are starting to question.

(Two Berardi pieces I felt gangly in were in the human world, problems are not solvable as the process of healing is interminable and economists are more priests than scientists. Who knows, I might grow into them yet.)

Some economists are proposing that the high-tech end to capitalism is just around the corner. Saying data will replace the price system as the “economy’s chief organizing principle.” Morozov says phooey. Data is capital. It accumulates with every touch of a screen. That accumulation will remain the principle organizing the economy chiefly.

So, if a more humane system is indeed to be preferred, the right move is towards the “broader ecology of modes of social coordination.” Competition isn’t what we want to take with us into jungle of digital data. As we get moving, attention must be paid to our “feedback infrastructure”—to producing data democratically, instead of waiting to see where it winds up.

I like Morozov’s style, too. It accentuates just where institutions could use a good reform. I wish it suited my obstinate body. What can I say? If you know me, or have been reading me closely, you’ll get why I’m partial to Berardi’s loose-cannon largesse.

Why I’m luxuriating in my we should focus less on the system and more on the subjectivity that underlies the global semio-cycle.

Why I’m letting my the possibility of a radical rerouting is inscribed in the cooperation among cognitive workers worldwide do the talking.

Why nothing’s coming between me and my those who have the potency to disentangle the content of knowledge and technology are those who produce this content: the cognitarians. Disentangling their activity and their cooperation from the gestalt of accumulation is the only way.

One thing I appreciate about working at a bookstore is the dress code. I wear what I want. Usually, that’s jeans and a collared short-sleeve. I also enjoy being behind the counter. I really like most of our customers, with whom I have lots in common. But I feel the greatest affinity with the mart’s janitors and cooks and drivers. They wear uniforms and work very hard. It’s nice giving them our employee discount when they buy books.

Cognitive workers who don’t see themselves as cognitive workers might not see themselves as cognitive workers because a machine could never do their job. At least that’s what I’ve seen in shop windows.

A lot of people still wear Margaret Thatcher. Her clothes say “people realise that their future depends on loyalty to and cooperation with their own company,” and “excuse me what makes you think that life will ever be easy in the world we are going to live in,” and “economics are the method; the object is to change the heart and soul.” At least younger folks find them ghastly. It seems we’re looking for nontraditional designers like Berardi instead.

Look out for more of us strutting around in getting rid of the trap of working does not mean that we will then do nothing, and we will do what contemporary society needs more: care, education, affection, environmental decontamination. We’ll be passing out pins and buttons like the task of autonomous thinking is no longer to limit the sphere of automation but to inscribe social interests (as opposed to capital interests) and human goals (as opposed to technologically automated goals) in the global machine.

In school I didn’t major in fashion. I learned little bits here and there, but only ever by looking. It wasn’t clear to me that I could touch the fabrics, press them to my skin.

Some clothes are flashy, others are staid. Some are unflattering, others are as if tailored for you. It’s okay to go shopping for new ones. It’s okay to replace hand-me-downs. You can even learn to make alterations. I’m both embarrassed and excited to only be realizing this now. There’s nothing like the right fit.

I know I wouldn’t be thinking about clothes if I had a uniform. Or if I didn’t visit Twitter so often. It’s a perpetual catwalk there, a doll house. Everyone’s either playing dress-up or hawking their wares.

It took me a while to try on Berardi. He was an influence on Mark Fisher, another favorite I modeled briefly in this space. (Here are the maestros, talking shop in 2013.) I wouldn’t have ordered a Berardi wardrobe were his distributor not offering half off. Had he not put out some new samples for this dark spring.

What does it mean to be convinced? What does it mean to be moved? What does it mean to find meaning? What does a world worth working towards look like? What does that work feel like? What should that work cost? These are but some of the questions to ask next time you go shopping.

Most of our outfits are in tatters right now. If you’re cold, I have some blankets to share. The trauma will not be a mere cultural breakdown. And this trauma will transform the relation between emotional and cognitive dimensions. And the direction of this transformation is not prescribed: it is the stake of the future game.

I’ll be trying on more new clothes soon. But I think that, in my closet, hanging next to my Raymond Williams, there’ll always be some Berardi. Pieces like the future is not prescribed but inscribed, so it must be selected and extracted through a process of interpretation. And the meaning of interpretation is to express, to bring forth what is inscribed, to translate from the language of inscribed material possibility to the language of signs and of communication. You can borrow them any time.

This was Sintext VIII. (Just me in italics now.) Thanks for reading.

There are many events, conversations, affordable materials on offer this month. I’d be thrilled to pass along links, or even get a reading group going. Get in touch. Hearing from you always means a lot to me.

More in two weeks.

Sintextually yours,

Marc